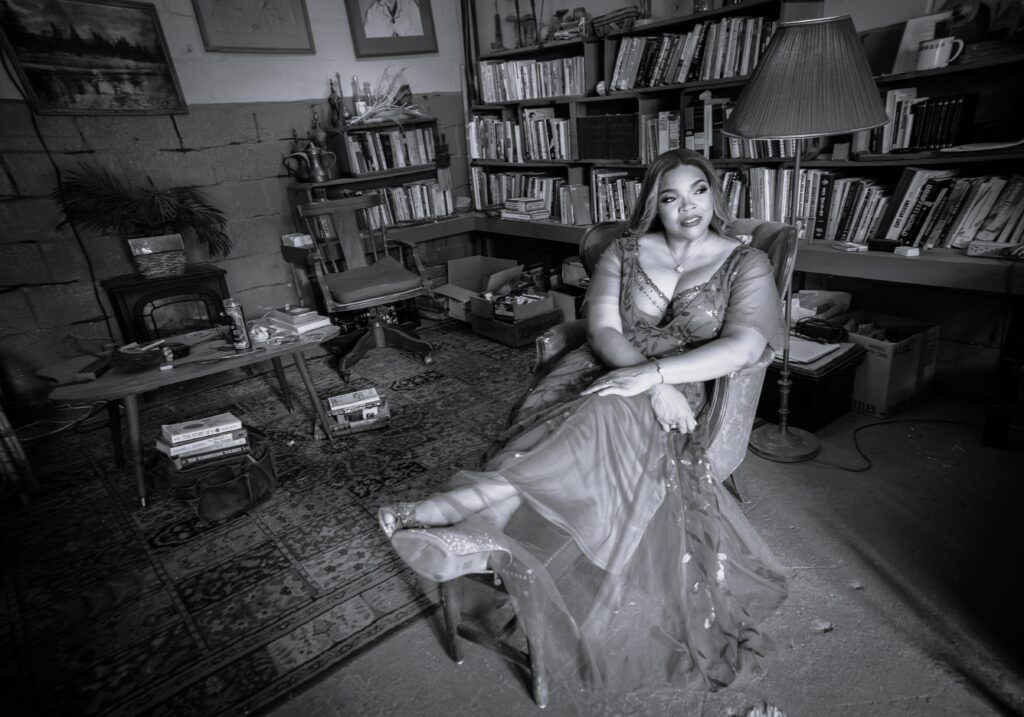

Candice Ivory and Memphis Minnie: a stunning duo

by Philippe Prétet

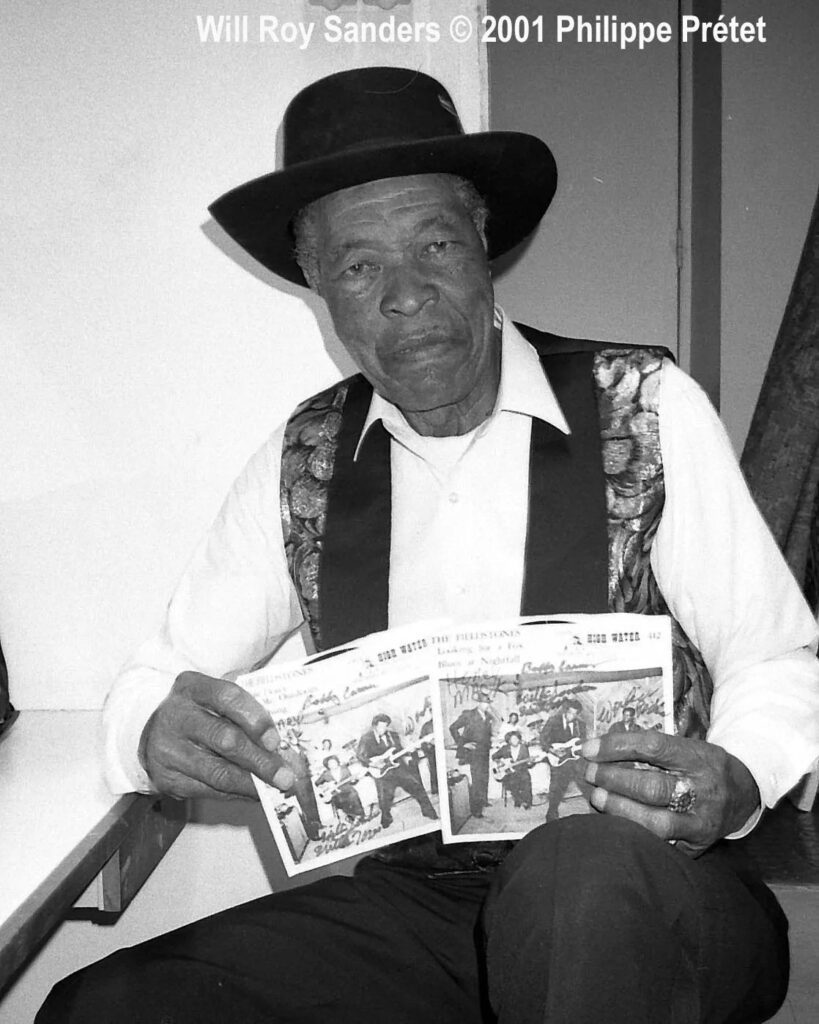

On the occasion of the release of her latest album “When the Levee Breaks: The Music of Memphis Minnie (Little Village Foundation), The Queen of Avant Soul aka Candice Ivory shines the spotlight on one of the blues’ greatest artists: Memphis Minnie, who, paradoxically, is rarely mentioned in the blues gotha. In fact, Candice Ivory, singer and multi-instrumentalist, is at home on piano, organ and percussion. She had long intended to record an album with the lyrics and music of Memphis Minnie. She owes her early successes to her great-uncle Will Roy Sanders (1934-2010), guitarist of the legendary Memphis band The Fieldstones, to whom she owes an unwavering love. Candice had to wait (euphemism) to express her youthful talent. That is, until the planets aligned in 2023, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of Lizzie Douglas’s death at the age of 76 (June 3, 1897 – August 6, 1973). Having grown up in a church and jazz environment, in a family of mostly male musicians, she sought out female role models to express her deepest personality.

The decisive factor was the budding friendship between Ivory and Hunter, a musician equally steeped in jazz, soul and Delta blues. Candice Ivory’s story with Memphis Minnie thus became obvious over time, almost initiatory, as if to get to know herself better. This captivating atmosphere can be felt both in the choice of songs (twelve) on her album and in their highly personal interpretations, far removed from insipid, flavorless copy/paste. Memphis Minnie is like a beacon for her, her patron saint of the blues in her own words. It was Charlie Hunter, as producer, who said: “I understand Candice Ivory as an artist, and this music is not one-dimensional“. Candice Ivory in concocting her fetish album wanted to respect Memphis Minnie as an innovator, showing the innovation she inspired. “I simply wanted the brilliance of the compositions and vocal melodies to shine through,” she adds. In search of a real connection with her mentor, she faced a real challenge in a male-dominated world to make her project a success. Full of determination and convictions, resolutely post-modern and forcefully pushing back the dusty walls of déjà-vu as a necessity, she is a fine promise of the blues women of Saint-Louis Missouri, and one to be reckoned with from now on.

Candice, your family was steeped in gospel and jazz culture, and you also grew up on Beale Street in Memphis. What were those years like? Looking back, what do you remember about them?

I was always exposed to a diverse group of musicians, both within my family and outside of it. In the summer, I spent a LOT of time church-hopping in choirs with my grandparents, aunts, and uncles. During the rest of the year, I sang in choirs at school and at my dad’s church. I sang with a big band, founded a professional jazz trio and quintet at the age of 14, and had a regular gig on Beale Street with a band called CYC by 15. What I remember most is all the encouragement I received before I became a professional musician. After it became apparent that I was going to pursue music, it seems like everyone became a little concerned about how I could do it (laughs).

You come from an illustrious family of musicians who shaped the secular and sacred sounds of Memphis. Your great-uncle was the singer and guitarist Will Roy Sanders of the Fieldstones, one of the leading blues groups in Memphis from the 1970s to the 1990s. How has your “emotional” relationship with Will Roy influenced your life?

Everyone in my family knows that Will Roy was my favorite great-uncle. It’s just a known and understood fact. There were lots of reasons for this, but the one I like to emphasize is that we had this secret world outside of the family. We knew each other as professionals and as friends. My family really didn’t know the extent of Will Roy’s work in blues, nor did they understand how seriously he took it. Also, everyone was preachers or extremely religious, so this basically created a kind of wall between our blues life and everyone else. He was heavily judged for his lifestyle choices. Between us, we didn’t have that sort of judgment. We just let each other be who we were in our blues world—and over there he was the man! I would drive him, my great-grandfather, and a few of my older cousins around so they could drink and listen to the blues. It’s ironic that the first single on my album is “Me and My Chauffeur” because I certainly was a chauffeur most of my young life!

Do you have an unusual anecdote to tell us with Will Roy?

I have several but for the sake of brevity, I’ll tell one that I just heard from a cousin a few days ago. My cousin Earnest witnessed this. My great-grandfather (Will Roy’s dad) was the person who got him started in the blues, and they used to hang out together. At some point when my great-uncle was in his early twenties, he was busking outside of a juke joint while my great-grandfather was inside socializing (this was a common occurrence, because my great-grandfather had been taking Will Roy around to nightclubs and leaving him outside, even when he was a young boy—which is how he began playing music). On this particular night, there was a commotion inside the juke joint. Eventually the commotion moved outside the juke joint, and it was my great-grandfather and another man fighting intensely. Then my great-grandfather proceeded to take Will Roy’s guitar out of his hands and use it to attack the man he had been fighting, beating him over the head and knocking him unconscious. Will Roy cried out in anguish about his now-broken guitar, a new instrument that he had just purchased. My great-grandfather then said, in a voice I can hear very easily in my head, “Shit son, I’ll buy you a new guitar, but didn’t you see that fella whippin’ my ass?!” I’m pretty sure he did reimburse Will Roy for the guitar that he destroyed.

You grew up in the church, and by the age of eleven, you had singing in a choir that included the future R&B superstar D’Angelo. Can you tell us more about this encounter, which seems to have been a sort of landmark in the history of your recent album?

My father was appointed as the head of a youth and young adult ministry at a church in Richmond, Virginia. One of the members had a son who went to high school with D’Angelo (whom we called Michael then), and he was invited to be the pianist and choir director for the youth and young adult ministry. Now as a kid, I would sit at any piano next to anybody. It was no different with him and he was very kind about it. He would show me new songs he had learned. I would teach him songs, too, and sometimes he would have the choir sing them. When I wrote a song, he would show me which chord voicings I could use. This was so kind and thoughtful for a young man—really just a teenager—who was about to sign a record deal with a major label. He was using the money he earned at the church to purchase new instruments and things like that. I spent countless hours at rehearsals with him learning aspects of his approach to music, though I did not know fully understand it at the time. He and my mom used to sing duets on a few songs, and I really loved those Sundays. On certain Friday nights we would host parties at our house for everyone in the choir, and D’Angelo joined us, cooking in the kitchen. When he finally left the church after accepting his record deal, the choir never sang the same way. He brought so much to the choir, even as an eighteen-year-old—I never forgot that.

Beside composing and singing, you also play a wide range of instruments, from piano and organ to percussion. Where does this passion come from?

As early as I can remember, I have always had a passion for music. I always listened to everything. My parents had to tell me to turn the radio off at bedtime, because I wanted to listen to it all night long. Almost everyone in my extended family could sing, and if they couldn’t, they would host a talent show and sing anyway. At picnics and family reunions, we always had cousins and Will Roy playing in a blues band. All the old timers wanted to see the little kids dancing in front of the band. Always family friendly. My dad plays bass and my mom studied classical voice. After she had children, she ended her formal studies, but she continued to sing in church. Choirs and evening church programs were always a part of my young life. There were several musicians in my family and while some chose to play secular music, we ALL had to be in church too. That means if cousin Richard or whoever else wasn’t at church to play drums or piano, etc., anyone should be prepared to step into that role. If the church you were at didn’t have a piano, you still need to be able to sing your song, regardless of any obstacles that may be put in your way. So naturally all this choir singing and church-hopping caused me to think of music constantly. In grade school I started playing cello, then the trumpet. Since then, music has always been at the forefront of my thoughts and dreams.

What does Lizzie Douglas (June 3, 1897 – August 6, 1973), aka Memphis Minnie mean to you?

Lizzie Douglas represented to me an archetype of a world that I understood—a world that contained virtually no women. On Will Roy’s side of the family, I was the only granddaughter. That was the side of the family where I learned the blues, and in that family, women had very specific roles—like the mute Black characters in the Tennessee Williams play Baby Doll. You saw them, but they had no voice. I call Memphis Minnie my patron saint of the blues. She was like a beacon of light for me.

There seems to be an amazing feeling between you two ? Correct ? Why ?

I think I tried to understand her so I could better understand myself. Together, our voices have amplified one another. Lizzie was able to navigate a tough and unfriendly terrain, coming from abject poverty in the middle of Mississippi to become one of the most distinguished voices in the blues canon—yet her accomplishments lay in the shadows. Minnie is our Frida Kahlo! We should see her image everywhere and they should be as ingrained in our mind as Robert Johnson’s photo with his hat and guitar. I am so thankful that Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes wrote about her, because reading those stories as a child enabled me to reconnect with her as an adult. I’m also a serious admirer of Hurston. Her work has heavily influenced mine. It has been part of this album also. I took pilgrimages both to Minnie’s grave and to Zora’s residence during the making of this album to pay my respects.

You pay a heartfelt tribute to Memphis Minnie. Instead of imitating your predecessor, you has embarked on a reinterpretation of the song, making it perfectly relevant today. In fact, this entire album shines through Candice Ivory’s artistic vision. Is this what you think?

If I had not been myself in this situation, ya’ll would be calling me Lil’ Memphis Minnie, and she would be laughing at me and calling me a poser! I consider myself a southern surrealist, because for me, art and music are everything. I ate and drank and inhaled Minnie for a time during this process. I wanted to imagine how she would approach everything. Life, love, dress and style, everything. I thought about the parallels of our lives and what events we have lived through. It was an absolute joy to work on this project, and I felt that she would have enjoyed it too. I tried to make sure the songs I sang reflected our energy and experiences.

Why is it so important for you today to revive several Memphis Minnie standards on your new album, even though she’s not part of the blues gotha? Should this be seen as a symbol or as a commitment to transmitting the values of Afro-American music into the 21st century?

There is no reason she shouldn’t be part of the blues gotha. This album is a direct statement that she belongs there, and in the rock gotha as well. Based on her vocal influence from Louis Armstrong, we can say that she belongs to jazz too. We need to ensure that no one who belongs is omitted from the pantheon, and certainly not Memphis Minnie.

It seems that the crucial factor was the budding friendship between you and Charles Hunter, a musician equally steeped in jazz, soul and Delta blues. For example, the eponymous song “When the Levee Breaks” is revisited. It is punctuated by bewitching percussion and magical incantations. You use the unbelievable imagination for another Minnie hit, “Me and My Chauffeur Blues”. The same for “Bumble Bee” recast with a gentle Taj Mahal-inspired reggae groove. That’s reason why Charles Hunter’s signature touch is perceptible in this album. Agree ?

I definitely agree! Minnie was an excellent guitarist and to this day, even accomplished musicians struggle to play her music. I just wanted the brilliance of the compositions and the vocal melodies to shine through. I did not deviate from Minnie’s melodies at all, which was very intentional. Charlie Hunter was able to take that approach to another level with his production skills and his understanding of who I am as an artist. He represented Kansas Joe McCoy, who was a very important part of Minnie’s history. She had the ability to hand-pick excellent musicians, and in this case, it was her husband. A high level of trust, lack of ego, and sincere commitment have to be there if you’re going to record with someone that much. Charlie had been studying Blind Blake and I was studying Minnie, but we both also have blues backgrounds which we haven’t “promoted” (laughs). With the team Charlie assembled in DaShawn Hickman, Atiba Rorie, Brevan Hampden, and George Sluppick, there was a great depth of musicianship, and that is one reason that album sounds the way it does. We all connected on so many different levels through the music and that was Charlie as a producer saying, I understand Candice Ivory as an artist, and this music is not one-dimensional. We wanted to respect Memphis Minnie as an innovator, by showing the innovation she inspired.

The new generation of Southern blues musicians is brilliant, including Christone “Kingfish” Ingram or Trenton Ayers, who will soon be releasing his first album. However, young blacks aren’t as involved in the blues as they used to be. It’s worth noting that there are very few young women embarking on a career. What do you think of this situation?

I think the lifestyle has always been difficult. It has always been a rough world for women to navigate. I do see aspects of that changing. I have been reluctant to work in it for this reason! I’m here because I’ve arrived at a time when a voice like mine is needed to help amplify other voices. In this case it’s generations of people, women, and especially Memphis Minnie.

What are your future plans?

I think you are called to the work you’re meant to do. I’m called here at this time to do this thing. I’m planning to do some performing overseas in 2024. In the meantime, I am in my studio practicing, teaching, and painting. I’m working on some original music and doing some recordings. Jimmy “Duck” Holmes has me exploring Bentonia-style blues right now, and I am pretty captivated with that. He has been a real mentor to me through this project, and now he and I are revisiting some lessons that he received directly from Jack Owens. Beautiful stuff. I have been asked to put When the Levee Breaks on vinyl, so now I need to figure out how to do that. After performing at the King Biscuit Blues Festival, I am really looking forward to touring more. I had a great time with my band and that has me thinking about writing new material

Is there any final question you’d like to have answered that isn’t in this interview?

Thanks so much for this interview, Philippe! The only thing I haven’t mentioned is how overwhelmed I am at the response to this record. I think Memphis Minnie would be proud. I know that I am so proud to be part of a significant tribute to a Goddess in our Blues pantheon. I want to thank everyone for enabling me to do that and for all of the love and support. It truly means a lot.

Comments are closed